| I would like to present a collection of writing related to the 53rd International Art Exhibition, commonly referred to as "la Biennale di Venezia" or "the Venice Biennale", specifically devised to address particular work(s) or artists. This years exhibition was titled "Making Worlds", directed by Daniel Birnbaum. My personal attendance at the exhibition in it's multiple venues and stages throughout Venice, Italy (Arsenale, Giardini, among others) took place in early September of 2009. | ||

For "Making Worlds", Birnbaum included in his directors statement, "When Fare Mondi Making Worlds brings back expressions from a recent past it is never for nostalgic reasons but in order to find tools for the future and the make possible new beginnings."

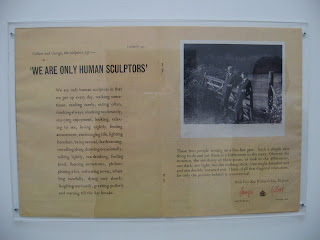

This "magazine sculpture", originally published in a Sunday Times color supplement in 1971 ("Two Text Pages Describing Our Position"), was featured among the curated works comprising the central exhibition at Giardini. Dated nearly thirty years ago, from a relatively early point in the collective career of the England based duo, this piece positions itself in a proactive, yet simultaneously inconspicuous, way among the works.

Displayed simply upon the wall behind a sheath of glass, a quality of aged, archive-defying paper is first evident upon immediate inspection. A crease assists in indicating that this document, this work, was originally folded, as do the staples in the paper's middle. "Gilbert and George, the sculptors say–," begins the left-page, followed by the bold statement in capitol letters, "'WE ARE ONLY HUMAN SCULPTORS".

This document created by the artists insists on two instances, in close succession, that Gilbert and George are in fact sculptors or, at least, would commonly refer to themselves as such and are intent on making this claim known.

Firstly, they address their two-man collective in a third-person narrative tone. Following is an emphasis on the statement, a proclamation regarded as the pinnacle of a larger quote made up of supposedly quantifiable evidence and validation in proof of the claim.

The question could justly be raised as to whether or not the art which lies in this piece, if any, could be found in the use of the linguistic components describing artistic activity. Language exists as an actualized material in this piece, printed and distributed, activating the work through textually-based information. A single sentence, organized by commas after short phrases or single words, alludes to the everyday, to activities that could rightly be attributed to a definition of personality. Possibly, the term "human sculptor" refers to a material followed by it's right of agency, a most direct and literal interpretation of the notion.

Perhaps the self-referential quality of the language is a result of the work. That the nature of Gilbert and George's sculptural practice is constantly turned in on itself becomes integral to recognizing it's intricacies, it's obstinate denial to admit or create any distinction between everyday experience and art. Also, a suggestion is inherent in this piece that one may play an active role and become a participant in this paradigm through a certain level of awareness, as the notion of localized responsibility can be paired with that of authoring and accounting for, or sculpting.

For this magazine advertisement to exist in it's preserved state as a glimpse into a moment past, an event occurring alongside the reading of the Sunday Paper, allows for it be appropriately disassociated with the present, that it is easily enough recognizable as historic, essentially a document of a larger action seen through by the two artists, though still supposedly with enough content of it's own to admit it into a predominately contemporary dialogue of art.

In this we can evidence a shift in meaning; not merely in it's decontextualization, but rather in it's reconstitution, an understood history and career proceeding the relic of '71 which speaks to a level of integrity and artistic practice calling for current examination.

Michael Elmgreen and Ingar Dragset

|

No comments:

Post a Comment